Chukat: Death does not defile

- Samuel Lebens

- Jun 24, 2020

- 15 min read

Updated: Jun 25, 2020

In this week's reading, things continue to unravel for Moses. First of all his sister dies. In the aftermath of her death, the Israelites complain of thirst. According to the Rabbinic tradition, the camp had access to a miraculous portable well that traveled with them. But its water flowed only in the merit of Miriam. When she died, the water ran out.

The next calamity occurs when Moses and Aaron are commanded to assemble the Israelites in front of a rock from which they would miraculously draw water. Something about the way this deed was done lands Moses and Aaron in terrible trouble. Perhaps it was because they lost their cool, perhaps it was because they presented God as angry with the Israelites when he wasn't, perhaps it was because Moses hit the rock to release the water, when he had actually been commanded to speak to it.

Whatever the exact nature of their wrongdoing, the result was a terribly harsh seeming edict from on high: like the rest of the men (women were not included in the decree) of their generation (except for Joshua and Calev), it was decreed, in the wake of this incident, that Aaron and Moses would die in the wilderness; they would not reach the promised land. And indeed, in this week's reading, Aaron is laid to rest. Moses is left without siblings.

The reading also contains a plague of serpents sent to punish the Israelites for yet more complaining; this time about the food -- as they tired of eating manna each and every day.

After detailing various detours, spurned overtures of peace, and military victories, this week's reading concludes with the Israelite camp finally reaching the eastern bank of the river Jordan; the border of Israel; a river that Moses wouldn't be allowed to cross.

We now have a picture of the narrative arch of this week's reading. But I skipped the opening section. The opening of the reading documents a bizarre ritual in which a red heifer is slaughtered and burnt. Her ashes are then crushed into water, creating a liquid used to purify people from the highest levels of ritual impurity. To be sprinkled by this water is to become pure, but, even more bizarrely, the person who does the sprinkling is rendered impure by the sprinkling ritual itself. It's all very odd. But it's also very out of place. What does any of this have to do with this week's narrative?

Quite rightly, last week's reading concluded with a re-assertion of the role of the tribe of Levi, and the role of the Priests, in the Tabernacle. That role had been questioned by the rebellion of Korach. But the ritual of the red heifer is not a restatement of anything that came before, nor does it come especially to assert the authority of the Levites and the Priests. The red heifer seems out of place. Indeed, this section seems to belong to the book of Leviticus, and its purity code. What's it doing here?

In the Talmud, Rabbi Ami suggests that it is indeed out of place. It should have been in the book of Leviticus but was instead appended to the death of Miriam to teach us a lesson. The lesson is that the death of the righteous atones for the sins of Israel just as the sacrificial services of the Tabernacle did. This teaching is cited by Rashi in his commentary to this week's Torah reading.

This is a problematic answer, to say the least. First of all, the ritual of the red heifer isn't directly associated with atonement. Its function is simply to remove a type of ritual impurity; and ritual impurity isn't inherently sinful. If you bury the dead, you'll become impure, but you've done nothing wrong at all. And though it's true that ritual purity is required in order to bring sacrifices, and the sacrifices do atone for sin, if God had wanted to teach this lesson, he could have juxtaposed the death of Miriam with the laws of the sin offering rather than with the laws of the red heifer.

Moreover, the notion that the death of a righteous person can atone for the sins of other people is disturbing. I don't deny that it's true. But I do contend that there are all sorts of theological and ethical problems that stand in the way of our understanding how the death of one good person can play a role in atoning for the sins of other people. Perhaps those obstacles can be overcome (and of course, a great deal of Christian theology is based upon the notion that the death of a righteous person can bring atonement to others). But it is, at least, a difficult notion.

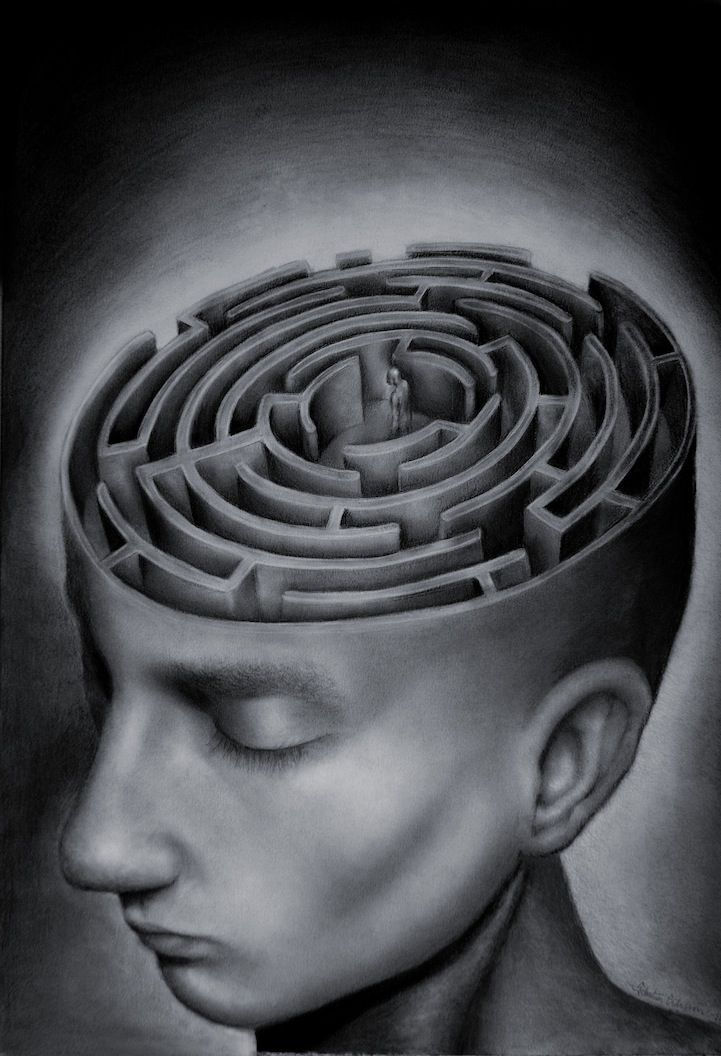

So, if we're uncomfortable with Rabbi Ami's answer, we should ask the question again. Why is the ritual of the red heifer located at the start of this reading? Perhaps we can appeal to the fact that the ritual of the red heifer is considered to be the archetype of a commandment that human beings cannot understand. King Solomon was granted supernatural wisdom, but according to the Rabbis, even he couldn't fathom the ritual of the red heifer. This week's reading includes all sorts of divine decrees that we don't understand. We don't understand why people have to die, or why Miriam wasn't granted the opportunity to reach the promised land, or what Aaron and Moses did wrong in this week's reading and why it merited such a harsh punishment (although, we'll return to this issue in the book of Deuteronomy).

As if to note the impenetrability of God's decrees in this week's reading, the reading as a whole is prefaced with a law that makes no sense to human reason. Indeed, the reading is called chukat which means something like "statute" or "decree", and is the word we tend to use to label the commandments that human reason cannot fathom.

A question to which I promised to return, as we were learning the book of Leviticus, is this: what is ritual impurity? Is it something real? Is it out there in the world, or is it merely a legal fiction? Perhaps the most fascinating and elusive discussion of this question appears in a Midrash about the red heifer. I want to present the Midrash in its entirety and then break it down into its constituent parts. But remember: this isn't two Midrashim. The editor of Midrash Rabba presents the entirety of what follows as one integral whole; a single Midrash:

An idolater asked Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai, "These rituals you do, they seem like witchcraft! You bring a heifer, burn it, crush it up, and take its ashes. [If] one of you is impure by the dead, two or three drops are sprinkled on him, and you declare him pure?!" He said to him, "Have you ever had an epileptic seizure [literally, "have you ever been possessed by the spirit called Tazzazit]?" He said to him, "No!" "Have you ever seen a person have an epileptic seizure?" He said to him, "Yes!" [Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai] said to him, "And what did you do for him?" He said to him, "We brought roots and made them smoke beneath him, and poured water [on him] and [the Tazzazit] flees." He said to him, "Your ears should hear what your mouth is saying! The same thing [as is true of the Tazzazit spirit] is true for this spirit, the spirit of impurity [which is just another sort of spirit], as it is written, (Zachariah 13:2) "Even the prophets and the spirit of impurity will I remove from the land." They sprinkle upon him purifying waters, and it [i.e., the spirit of impurity] flees." After [the idolater] left, the Rabbi's students said, "Our Rabbi! You pushed him off with a reed. What will you say to us?" He said to them, "By your lives, death doesn't defile, and water doesn't purify. Rather, God said, 'I have legislated a statute; I have decreed a decree, and you have no permission to transgress what I decreed, as it says [about the red heifer] "This is a statute of the Torah." And why are all the sacrifices male, while this [heifer] is female? Rabbi Aibo [told] a parable of a maidservant's son who made the King's palace filthy. The King said, his mother should come and wipe away the feces. So too, the holy One, blessed be He, said that the heifer should come to atone for the deeds of the [golden] calf.

This Midrash divides into three scenes. In the first scene the idolater mocks the ritual of the red heifer. Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai defends the ritual in terms of Babylonian medicine.

Ancient Greek medicine tended to view illness as some sort of internal imbalance. Babylonian medicine, by contrast, tended to view illness as an attack from the outside. The external illnesses were personified as spirits or demons. Greek medical treatments sought to restore internal balance by consuming the right foods and by releasing certain fluids, as was the case with medicinal blood-letting. Babylonian medical treatments, by contrast, focused on cleansing the environment or the patient of the harmful spirits in question. Although both forms of ancient medicine can sound crazy and/or superstitious to modern ears, they were both onto something. The internal maladies of Greek medicine find modern expression in our understanding of genetic and congenital disorders. The demons of Babylon, by contrast, can be seen as ancient precursors to viruses and bacteria.

Rabbi Yochanan’s response to the idolater concerns the demon known as tazzazit which was, according to the Babylonians, responsible for what we would call an epileptic seizure. The science of the day prescribed burning roots near to the patient and sprinkling water over him. This wasn’t witchcraft. It was medicine. The epileptic patient, they believed, had been invaded by some external entity. Smoke and water could cause it to flee. Rabbi Yochanan’s point is this: the ritual of the red heifer isn’t witchcraft, it’s as scientific as medicine. What we call ritual impurity is a real entity that attacks us from the outside, just like bacteria and viruses. The Torah’s provides us with the way to rid our bodies of this foreign agent called impurity. That’s all that’s going on with the red heifer.

In the second scene of the Midrash, the idolater has gone. Rabbi Yochanan is left in the company of his students. They can’t believe that impurity is something natural. They can't accept that the ritual of the red heifer is a scientific treatment for the eradication of this foreign agent. They applaud Rabbi Yochanan for fobbing the idolater off with an answer that would satisfy him. But they are more sophisticated than the idolater. They want a real answer. What’s going on with the ritual of the red heifer?

In this scene, Rabbi Yochanan articulates a completely different theory of purity and impurity. In the most shocking words of the Midrash, he says “death does not defile and water does not purify.” In fact, he seems to pre-empt the rationalistic account of purity and impurity that Maimonides, centuries later, would endorse.

Purity and impurity don’t really exist. They are not a part of the natural world, as are bacteria and viruses. Instead, they are purely legal categories. God didn’t want us to go to the Temple too often, for fear of its losing its power over us. By creating the legal categories of purity and impurity, forbidding entry to the Temple for those who are impure, and instigating various rituals for the removal of impurity, God ensures that visits to the Temple will not be too frequent.

As well as regulating our visits to the Temple, these laws can also teach us various lessons. For instance, by associating death with impurity, the Torah could articulate the value of life and the metaphorical toxicity of death. By regulating sexual relations around the legal category of menstrual impurity, the Torah could also promote relations between spouses that wouldn’t be too reliant too often on sexuality and lust. But none of this means that purity and impurity actually exist.

To sum up the theory of Maimonides we could use the words of Rabbi Yochanan: “death doesn’t defile, and water doesn’t purify. Rather, God said, ‘I have legislated a statute; I have decreed a decree.’” Indeed, this Midrash could serve as an important proof-text for the Maimonidean theory of purity and impurity.

The Midrash then moves on to a third scene that seems to have nothing to do with the first two scenes. Indeed, it seems as if the editor of the Midrash has purposefully tagged on an epilogue to the main body of our Midrash. This extra scene contains Rabbi Aibo’s theory as to why the red heifer has to be a female when all of the other sacrifices were, apparently, male. Perhaps the connection to what came before is this: if water is enough to cause a spirit to flee, why do we add the ashes of the heifer? The answer is symbolic. The ashes of the heifer symbolise a certain sort of responsibility that we must take for even very indirect consequences of our actions (like the waste products of our young children).

Having laid out the three sections of the Midrash, let me ask a question: to whom was Rabbi Yochanan telling the truth?

On a simple reading of the Midrash, the answer is obvious. Rabbi Yochanan fobs off the idolater and tells the truth to his students. The idea that purity and impurity are real properties out there in the natural world is a naïve literalism. It can be fed to the masses to pacify their confusion but in actual fact there is no substance to the notion of purity and impurity beyond the law; they are nothing more than legal categories, and that’s enough. But should the students trust the answer of their Rabbi?

Rene Descartes was worried by the extent to which his knowledge of the world relied upon his senses: vision, hearing, smell, taste and touch. The problem was that all of those senses are liable to deceive a person. A tower might look small, when in fact it’s very tall, but it's also far away. And indeed, we all know how convincing an optical illusion can be. But if the senses are sometimes deceptive, then how can we ever trust them? As Descartes memorably put the point: “it is wiser not to trust entirely to anything by which we have once been deceived.”

Let’s take Descartes’ advice. If we accept that Rabbi Yochanan was willing to deceive the idolater in conversation, then how can we trust that he isn’t deceiving his students? Perhaps he told the idolater exactly what he really thought only to find that his students considered themselves too sophisticated to accept that the natural world contains purity and impurity. Accordingly, perhaps he fobbed his students off with some reductive rationalistic explanation designed to satisfy their intellectual hubris. Once we know that Rabbi Yochanan is willing to play tricks on those who ask him questions, how can his students be sure that he isn't tricking them?

Far from being a proto-Maimonidean, on this reading, Rabbi Yochanan was a literalist about purity and impurity but gave his arrogant students a reductive explanation that would satisfy them. What evidence can we provide for this reading? Well, perhaps that's where scene three comes in!

By tacking on Rabbi Aibo's parable about the calf and the heifer, the editor of the Midrash is hinting to us that we shouldn't be too quick to accept the answer that Rabbi Yochanan gave his students. The impurity that the heifer comes to clear away is as real as the feces that was smeared all over the palace of the King. In scene 3, we learn that these are not empty rituals or legal fictions. Just as it had to be the mother to wipe away the dirt of the son, and just as only specific medication is suitable for the treatment of epilepsy, it had to be a heifer to purify our impurity; nothing else would do the trick. In other words, perhaps scene 3 is a hint to the reader: don't be too quick to dismiss the answer that Rabbi Yochanan gave to the idolater; perhaps it wasn't the idolater that he was fobbing off; perhaps it was his students!

But of course, in addition to this reading, the Midrash invites a completely different reading. On the alternative, and more natural reading, Rabbi Yochanan is telling his students the truth. He really is a proto-Maimonidean. He really was fobbing off the idolater. But if that's the case, then what is the function of the third scene of our Midrash? Well, perhaps the point is this: even if it's true that the purity code is a legal fiction, it doesn't mean that it's an arbitrary fiction. The details might be pregnant with symbolic meaning, even if there's no such thing, beyond the law, as real impurity.

On this reading, it needn't be arbitrary that death is what defiles. Even though there isn't any actual impurity in the world beyond the law. The fact that the law treats death as toxic comes to teach us something about the value of life. Likewise, the fact that it's a female heifer selected for the ritual of purifying people needn't be arbitrary, even if it's all a legal fiction. The choice of the heifer comes to teach us a lesson about responsibility.

Maimonides himself was accused of treating too many of the details of Jewish law as arbitrary. It's all well and good to say that impurity is a legal fiction, but how does that explain all of the various details of the law? How does it explain why some things render you impure and some things don't, and why some varieties of impurity are more severe than others, and why some forms of impurity last longer than others? Too often, the Maimonidean account leaves these sorts of details unexplained. But, perhaps the third scene of our Midrash offers a response: even if impurity is a complete legal fiction, that doesn't mean we can't look to find the deeper meanings that each and every detail of the law come to symbolise.

We're surrounded by competing readings. If we trust the Rabbi Yochanan of scene 1, then we arrive at one understanding of scene 3. And, if we trust the Rabbi Yochanan of scene 2, then we arrive at a completely different understanding of scene 3. Moreover, if we take Descartes' advice to heart, maybe we should worry that Rabbi Yochanan wasn't telling the truth in scene 1 or in scene 2! Perhaps he merely told people what they wanted to hear in order to give the law a meaning that worked for them.

We want to know what purity and impurity are. We want to know if they are real things that exist in the world, or whether they are merely a legal fiction, and this Midrash has proven to be terribly frustrating because it yields to too many conflicting readings.

In fact, things get worse when we zoom in on scene 3. That scene begins by asking why the red heifer is the only female sacrifice. But the question is all wrong. First of all, the red heifer isn't strictly speaking a sacrifice at all. Its ashes are used to make a potion for purification. But the heifer itself isn't an offering to God. Secondly, female offerings were brought in the Temple; although its true that all of the communal offerings were male. Moreover, the stain of the golden calf was the stain of sin, and the red heifer doesn't come to wipe away sins. It comes to wipe away ritual impurity; and impurity needn't be at all sinful. And thus, Rabbi Aibo's whole parable lacks a certain sort of rigour that you might reasonably demand from the philosophy of Jewish law.

It's as if the only take home message that we can draw with any confidence from this Midrash is that when it comes to our question - about the nature of purity and impurity - you can pretty much say whatever you like, so long as, in the end of the day, you observe the relevant laws.

Of course, the fact that this is the only take home message might imply that our question doesn't matter. Who cares if impurity is a feature of nature, or a feature only of the law; our job is just to keep the law. The philosophy of law is unimportant. Say whatever makes you feel good.

But I think that there's a much more intriguing possibility to explore. Perhaps our Midrash is engineered so as to leave us thinking that it doesn't matter, not because the philosophy of halakha (Jewish law) is a waste of time, but because both answers to our central question are true. Once you recognise that the same God who legislated the Torah also came up with the laws of nature; once you recognise that for there to be an electron is just for God to will for there to be an electron; then the difference between a halakhic reality and a natural reality evaporates.

A £10 note has certain natural properties. Its area is 132 × 69mm. It is made of a polymer. These things are true of the note irrespective of what its worth. These properties of the note could be discovered by a physicist and/or a chemist. But the note also has a value as legal tender. It is worth 10 pounds. It gets that value, not from nature, but from various conventions and laws. Physics and chemistry alone cannot discover the value of a £10 note without some help from political science, law, and economics. So, in general, the distinction between natural properties and legal properties is clear and distinct. But what happens when the laws in question were written by God?

A dead body has certain properties that could be described by an anatomist or a biologist. These are its natural properties. In the halakha, it also renders things impure. Is that a natural property or a legal property? Well, since God is the legislator of both natural laws and Jewish laws, the distinction, which is stark in other contexts, evaporates. All that really matters here is "'I have legislated a statute; I have decreed a decree, and you have no permission to transgress what I decreed."

On this reading, our Midrash isn't saying that philosophy of halakha is unimportant. Instead, it could be read as making a profound philosophical point of its own: it doesn't matter whether you trust the Rabbi Yochanan of scene 1 or scene 2, because when the law in question is Biblical law, and the legislator is God, then the distinction between law and nature evaporates; and if that's what Rabbi Yochanan really believed, then he wasn't telling the whole truth in either scene.

What then becomes of scene 3? Perhaps the message is this: we live in a world that God spoke into being; and thus in Jewish law, and in Jewish life, everything that we see is saturated with religious significance. This significance isn't always found through rigorous argument. Scene 3 of the Midrash might be lacking a certain sort of rigour, but, at the end of the day, Rabbi Aibo saw, in the ritual of the red heifer, a message that was worth seeing. Sometimes, the significance of the world is discovered with the assistance of a more literary than philosophical sensitivity. As with reading a good novel, no detail of this world should be left uninterpreted. We creatures are gifted a certain sort of freedom of association that can help us mine this world for meaning. Nature and Jewish law are both the creations of one author, and everything is illuminated.

Comments