Tazria-Metzora: Spiritual Quarantine

- Samuel Lebens

- Apr 23, 2020

- 11 min read

Updated: Apr 24, 2020

A large part of this week's double reading deals with the diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation of people with a Biblical disease known as tzaraat. Traditional English translations of the Bible, following the Greek Septuagint, would regularly translate tzaraat as leprosy. But the disease described in the Bible simply doesn't fit the profile of leprosy.

First of all, leprosy is contagious. And despite the fact that the metzora (the person with tzaraat) was sent into quarantine, this had to do with their ritual impurity, rather than a concern for contagion. There's no indication that the priest, who inspects the metzora, is worried about catching the malady.

In fact, the Biblical description paints a picture of a disease that causes skin discoloration, and hairs within those patches of skin turning white. These patches can spread rapidly within two weeks. All of this is strikingly consistent with the symptoms of the skin condition known as vitiligo. Indeed, the similarities between tzaraat and vitiligo become even more pronounced once one filters in the Rabbinic description of the symptoms to be found in Tractate Negaim of the Mishna. These similarities led Yehuda Leib Katsnelson, in his studies of Talmudic medicine, to identify tzaraat and vitiligo.

Katsnelson was not the first to regard Tzaraat as a medical, rather than a, primarily, spiritual ailment. For instance, the Midrash suggests that a person's body contains a delicate balance between blood and water. When the water dominates over the blood, a person supposedly comes down with dropsy. When the blood dominates over the water, the Midrash suggests, a person comes down with tzaraat. To be sure, the Midrash says that these imbalances occur in response to a person's sinning. So, the causes are spiritual. But the ailment itself isn't supernatural. It's a bodily imbalance.

Despite what that Midrash tell us, the Torah gives us good reason to think that the ailment itself was more than just a fluid imbalance. The ailment was supernatural. Based on a traditional reading of Exodus 21:19, Rabbinic Judaism delegates medical matters to medical experts. If we're unwell, we may very well ask the Rabbis to pray for us, but we should also seek the help of medical experts. In fact, to seek the help of a medical expert is an halakhic obligation. And yet, when a person comes down with tzaraat, he's not supposed to visit a doctor. On the contrary, he or she is commanded to consult with a priest. The priest, and not a medical practitioner, is charged with the diagnosis of this ailment. The priest also determines whether the quarantine can end. Given the halakhic duty to consult a medical expert when stricken with a medical condition, this amounts to evidence that tzaraat is not a medical malady at all; not leprosy; nor vitiligo; nor too much blood. It is a spiritual malady; an illness that calls for a priest instead of a medic -- this observation was made explicitly by Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch. Moreover, the Biblical ailment of tzaraat is described as infecting clothes and buildings as well as people. Clothes and buildings are beyond the traditional remit of the medical sciences.

At this point, it's worth taking a step back and considering where we are in the narrative arch of the book of Leviticus. The book begins with some laws of animal sacrifice. Animal sacrifice is a difficult issue that stands at odds with contemporary, western, religious sensibilities. We'll come back to this thorny issue later in the series. But it isn't our focus today.

After the description of the laws of various sacrifices, the account of the inauguration of the Tabernacle, and the death of Aaron's sons, the book of Leviticus charts a very clear conceptual journey. Chapters 11-17 deal with the concepts of ritual purity and impurity. Chapters 18-27 deal with the concept of holiness. There is a progression from purity to holiness.

We are supposed to be punctilious in our ritual observances: animal sacrifices and the codes of ritual purity -- including dietary requirements, which divide the animal kingdom into pure species, which we're allowed to eat, and impure species, which we're not allowed to eat; and laws regarding bodily impurity. And yet, these observances are not an end in themselves. They are supposed to make room for the possibility of holiness. We'll talk more about holiness next week. What we should note for now is that the book of Leviticus, after the introduction of animal sacrifices, contains two codes of law: the purity code and the holiness code.

This week's reading falls in the middle of the purity code. This code starts out with animals. Dead animals, we are told, are a source of impurity. Dead human beings are perhaps the most central source of impurity. It's clear from this that impurity isn't a moral defect. First of all, there's nothing immoral about being dead! Second of all, we are commanded to become impure in order to honour and bury the dead. There's nothing wrong with that.

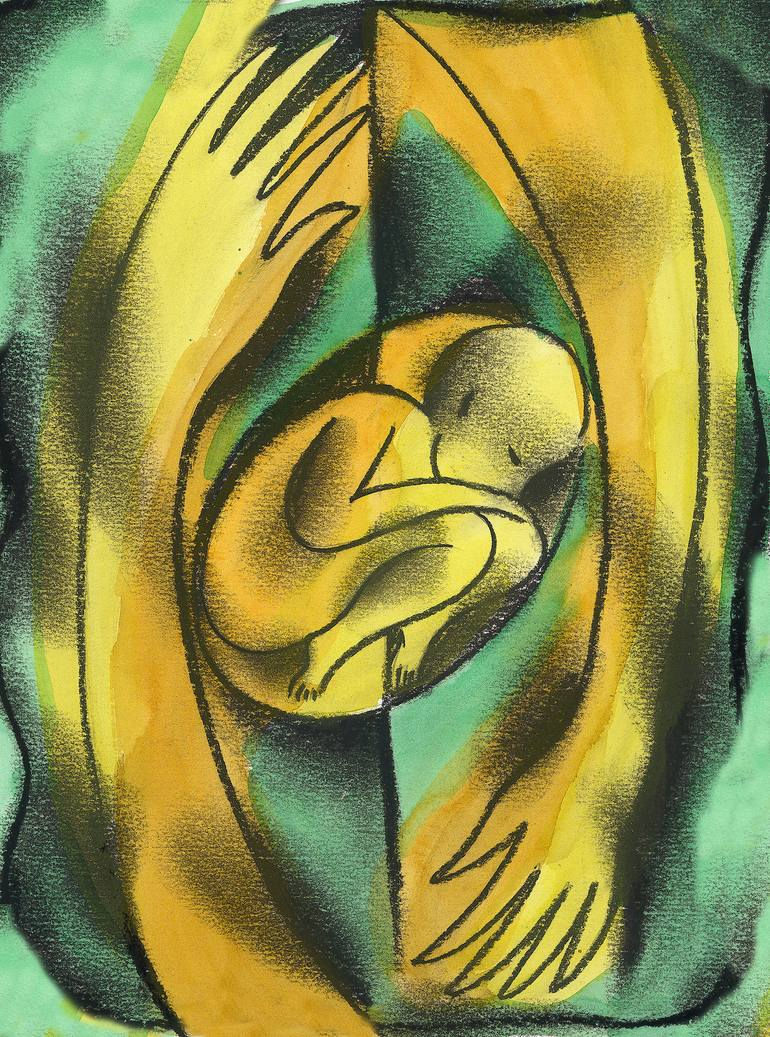

Then, at the beginning of this week's reading, we're told that a woman becomes ritually impure after giving birth. Conceptually, this makes sense. If impurity is primarily associated with death, then a pregnant woman, upon giving birth, has lost a life-force that used to live inside her. There is, so to speak, a reduction of life in her. This renders her impure. And since the woman is a symbol of life, because she gives birth to life, a mother who gives birth to a daughter, has, in a sense, lost something more that a mother who gives birth to a son. And so we see, a mother of a new-born daughter is impure for longer than the mother of a new-born son. For the same reason (we'll learn a little later on in the book of Leviticus), ejaculation renders a man ritually impure, and menstrual blood renders a woman impure. Again, there's nothing here about morality. Birth and intimacy are celebrated by Judaism, even though they render a person impure.

Whether or not purity and impurity are supposed to be real things, or whether they're supposed to be some sort of legal fiction, we'll come back to in the book of Numbers. But what I want to point out here is that the laws of purity almost force us to recognise the significance of life and death. The book of Leviticus seems to be saying that a culture should be fanatical about the value of life, to the extent that it ritualises the toxicity of death, if it wants to make space for holiness. The notion of purity comes before the notion of holiness.

So what is the Biblical disease of tzaraat doing here, conceptually, in the middle of the purity code; inserting itself abruptly between the Biblical discussion of the impurity of child-birth, and the later discussion of the impurity of various emissions (from semen to menstrual blood)?

One explanation, supplied by the Midrash, is that tzaraat appears at this juncture in order to teach us that the disease was a punishment for people who didn't abide by the purity laws regarding marital relations. Another Midrash, in a similar vein, tries to derive from verses in Isaiah, that tzaraat is a punishment, more generally, for sexual impropriety. These explanations would account for the placement of the Biblical discussion of tzaraat in the midst of its discussion of reproductive purity and impurity.

But perhaps the explanation is more prosaic. The discussion of bodily impurity starts with whole bodies, in the case of corpses; it moves on to a discussion of whole people giving birth to whole babies. Accordingly, before moving on to the emission of bodily fluids, which are entirely removed from the body, it makes sense for the Torah to describes the impurity of tzaraat which primarily breaks out upon a person's skin (although it can affect hair, clothes, and houses too). Tzaraat is less removed from the body than a bodily emission, so it takes precedence over the latter, in the Torah's purity code.

But, the idea of linking the disease to sin makes a lot of sense once you accept that this is a completely spiritual malady. We're talking, in the book of Leviticus, about the creation of a holy people. When all goes to plan, that holiness is supposed to run so deeply that a person out of kilter with his or her own values will break out in tzaraat; so in tune will be their body with their soul. For this reason, the fact that tzaraat is a Biblical disease that doesn't exist in our times is often taken, by the Rabbis, as a sign of our spiritual malaise.

If we were more holy, perhaps we'd be capable of breaking out in tzaraat whenever our actions came out of line with our values. But which actions exactly? Is tzaraat exclusively a consequence of sexual misdemeanors? Not necessarily.

Another Midrash teaches that there are seven causes of tzaraat. First it quotes the book of Proverbs (6:16):

Six things the LORD hates; Seven are an abomination to Him.

Rabbi Meir argues that this verse is referring to thirteen terrible things, since six and seven make thirteen. The Rabbis, by contrast, argue that there are only seven things under discussion, but that the seventh is so bad that it's equivalent to the other six put together. The proverb continues (Proverbs 6:17-19), listing the seven things:

(1) A haughty bearing, (2) a lying tongue, (3) hands that shed innocent blood, (4) a mind that hatches evil plots, (5) feet [that are] quick to run to evil, (6) a false witness testifying lies, and (7) one who incites brothers to quarrel.

According to Rabbi Yochanan, all seven of these vices are causes of tzaraat. The Midrash then brings a proof for (almost) every putative cause:

The scab on the head received by the haughty daughters of Israel, in the prophecy of Isaiah (3:16-17) serves as the proof that a "haughty bearing" can cause tzaraat.

The episode of Miriam receiving tzaraat in punishment for talking behind Moses' back (Numbers, chapter 12) serves as proof that a "lying tongue" (or, more generally, the sin of gossip) can cause tzaraat.

That "shedding innocent blood" is a cause of tzaraat, we learn from David's General Yoav (cf. I Kings 2:32 and II Samuel 3:29).

The affliction of King Uziah (II Kings 15:5) is supposed to serve as proof that hatching evil plots can result in tzaraat.

The affliction of Elisa's servant Gehazi (II Kings 5:27) serves as proof that "feet that run to do evil" can cause a person to come down with tzaraat.

Admittedly, the Midrash doesn't bring an independent proof that "bearing false testimony" is a cause of tzaraat, but this might be subsumed under the episode of Miriam, taken as a warning about the misuse of speech in general.

The tzaraat that blighted Pharaoh in the book of Genesis (12:17) [although, the verse only refers explicitly to mighty plagues] was, apparently, a result of the animosity that his actions bred between Sarah and Abraham. He "incited quarrels."

So: tzaraat is a miraculous spiritual malady. It has any number of potential spiritual causes: sexual impropriety of one form or another, or the seven sins listed in the book of Proverbs, or the ten sins associated with tzaraat in a subsequent Midrash (namely: idolatry, incest, murder, the desecration of the Name, blasphemy, robbing the public, taking what is not one's own, arrogance, the evil tongue, and the evil eye). But in the Jewish popular imagination, one cause is much more prominently associated with tzaraat than any other. That cause is the misuse of speech.

Perhaps the prominence of this cause boils down to the centrality of the story of Miriam in the popular imagination. The Torah explicitly commands us to remember that episode (Deuteronomy 24:9). Some have the custom of doing so, verbally, every day. But there are other reasons too. The Biblical treatment and rehabilitation of the metzora have led some people to think specifically about the misuse of speech. It's as if the rituals of tzaraat are specifically designed to comment upon the gossiper. Indeed, the Talmud (tractate Arakhin 16b) records the following discussion:

[It was asked] of Rabbi Ḥanina, and some say [that it was asked] of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi: What is different about a metzora, that the Torah states: “He shall dwell alone; outside of the camp shall be his dwelling” (Leviticus 13:46)?

The assumption is that the disease isn't infectious. After all, the malady is spiritual, and not viral or bacterial. So why must he be isolated? The following answer was offered:

He [caused] separation between husband and wife and between one person and another [i.e., he created rifts with his gossiping]; therefore the Torah says: “He shall dwell alone”

The isolation of social distance is a particularly fitting punishment for a person who has caused social distance with his speech. The discussion continues:

Rabbi Yehuda ben Levi says: What is different about a metzora that the Torah states that he is to bring two birds [as a sacrifice] for his purification (Leviticus 14:4)? The Holy One, Blessed be He says: He acted with an act of chatter; therefore the Torah says that he is to bring an offering [of birds, who chirp and] chatter.

As the metzora rejoins society, birds are offered up to remind the one who brings them that he can do better than the idle chatter of the twitterverse.

Between 1846 and 1860, a cholera pandemic (the third cholera pandemic of the 19th Century) ravaged much of Asia, Europe, Africa and North America. In 1854, it killed 23,000 people in the United Kingdom alone. In 14 years, it killed over a million people in Russia. One of the leaders of global Jewry, at that time, was Rabbi Yisrael Lipkin, better known as Israel Salanter.

When the pandemic was at its peak in Lithuania, many Jews started to point fingers and to blame the pandemic on certain sins and certain sinners. Rabbi Salanter patiently pointed out that tzaraat required, for its treatment, a period of isolation. The reason for this, he explained, was because the ailment was a consequence of evil speech. The sin isn't specifically that language was used to tell untruths. The sin, as Rabbi Salanter explained it, was that the gossiper is only interested in uncovering the sins of other people; never himself. The period of isolation, the spiritual quarantine of the metzora, is designed to convey the following message: "If you're such an expert at finding fault in others, leave the camp, sit alone with yourself, and use that expertise to discover your own weaknesses and sins."

After listing all sorts of sins that could cause tzaraat, the one that stuck (so to speak) in the popular imagination, was the sin of misused speech. Perhaps that's because it's actually not for us to say why a certain ailment comes to a certain person at a certain time. Sure, there could be all sorts of reasons, but the only person we should be pointing fingers at is ourselves.

I was especially moved by these thoughts this year as the entire world seems to be sitting in quarantine. Some have, indeed, used the opportunity to point a finger at others: blaming the pandemic on one alleged sin or another. But the weight of the tradition, I would contend, pushes us in another direction entirely. We don't really know why history unfolds as it does. We don't really know why last year we read this reading in synagogue, and this year we're reading it in isolation. It's certainly not for us to point fingers at anybody else. But, what we do know is this: we can use everything that life throws at us as an opportunity to point a finger at ourselves.

This needn't descend, God forbid, into unhealthy self-chastisement and self-loathing. In actual fact, the metzora leaves the period of isolation with an odd little ceremony that looks extremely similar to the inauguration of a high priest (compare Leviticus 14:17 and Exodus 29:20-21). A sinner (and we are all sinners) who goes through a period of self-reflection is welcomed back into the community as an honorary high priest; a religious luminary; an inspiration.

We can offer no theological account as to why this plague is blighting the world. We can only pray that it ends quickly, and that God blesses the work of the hands of the medical professionals and key workers on the front lines. But as we sit in the safety of the shutdown, and in the isolation of social distancing, we can take the opportunity to look at ourselves in the mirror, without the distractions of social proximity. We can come to understand better our strengths and weaknesses, and resolve to leave our quarantine, when the time is right, as better versions of ourselves; high priests on the road to holiness.

Comments